The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has affected digital advertising and marketing budgets across the board as companies have had to adjust to shifting consumer needs.1 While overall advertising spending is expected to decline from last year as marketers deal with these changing budgets, industry surveys indicate that digital advertising spending is expected to increase over 2019 figures, in some sectors by as much as 26%, particularly in the areas of search, social media, and connected TV.

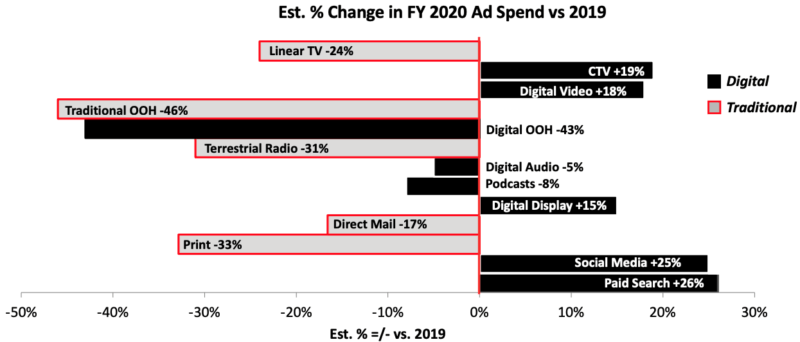

According to eMarketer, the three big players in the digital ad platform space are Google, Facebook, and Amazon, with a combined 68% share of total digital ad spending based on 2019 numbers.

In that same vein, while traditional media outlets can deliver large audiences, these audiences are generally very broad, comprised of many kinds of people with different needs and interests. Digital media allows for increased microtargeting, which allows advertisers to set narrower parameters for who will see their ads, maximizing the potential return on investment by serving their ads to these tailored audiences. This ability, along with shifts in consumer media consumption, is one of the major attractions of digital advertising.

Digital Advertising for the Win

During election season, politics and microtargeting intersect in the form of advertising to promote specific candidates and their platforms. Though for some it might be hard to imagine a time without social media having an influence in politics. In terms of U.S. presidential election cycles, this is really only the fourth to make use of social media and microtargeting as part of campaign communications strategies. The 2008 Obama campaign pioneered this approach for campaign communications.

The 2018 midterm election season saw overall spending on digital political ads reach almost $900 million.2 According to Advertising Analytics, the 2020 presidential cycle was expected to generate as much as $6.7 billion on ad spending across all platforms and mediums. Furthermore, approximately $264 million was spent on political advertising on Facebook in Q3 of 2020 alone, according to CNBC.3

Political Digital Advertising for Candidates

While effective for reaching desired audiences, the ability to microtarget audiences also means there has been a trend toward increasingly partisan political advertising on social media – instead of reaching undecided voters, it is often more about encouraging or maintaining existing supporters, as discussed in a recent Foreign Press Center briefing with the Wesleyan Media Project. This partisan trend is also in line with voter reports of their own news media selection, according to the Pew Research Center.4

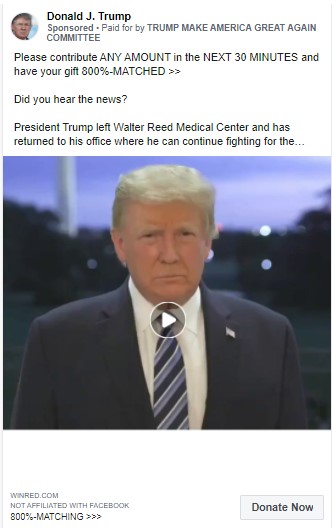

As of Oct. 26, this Donald J. Trump page ad (left) was the single most expensive Facebook ad of his campaign, according to Facebook data compiled by the Illuminating Project at Syracuse University. The campaign spent $325,000 and achieved 1 million impressions with this ad. The Joe Biden ad (right) was the most expensive Facebook ad of his campaign, spending $275,000 for 1 million impressions.

Digital Advertising Regulations

The Federal Election Commission regulates political ad disclosure requirements, which let voters know who paid for an ad. However, as with many areas of the law, the FEC regulations have not effectively kept pace with advances in digital advertising. This has led to a situation where, in effect, the responsibility to regulate disclosures of many of these ads falls on the social media and digital platforms themselves.

Consequently, FEC disclosures loopholes and the potential downsides of microtargeting in politics became evident in the months after the 2016 presidential election cycle. As a result, it came to light that foreign operatives had used social media, Facebook advertiser tools, in particular, to try to create unrest by appealing to partisan views in the form of memes and other content. This activity led to 13 individuals affiliated with the Russian troll factory Internet Research Agency being indicted on charges such as criminal conspiracy to defraud the United States.5 Research on political memes that I conducted during the 2016 election suggested that the internet memes are subject to partisan cognitive bias in message processing.

Changes to Digital Advertising Regulations

Because of these activities coming to light, beginning with the 2018 election cycle, many platforms took different approaches to political advertising on their sites. As a result, sites like Twitter and TikTok, are not allowing any at all, and others, like Google, limiting targeting options for political advertisements in the 2020 campaign season. The 2016 experience also led Facebook to implement stricter rules around disclosures and targeting of political advertising on the site and the creation of its Ad Library, which allows people to search for information about the ads run on its platform. Facebook also announced it would not accept political advertising during the seven days leading up to the Nov. 3 election.6

Political Advertising and Big Tech

While a desire to be good “citizens” likely played some role in these decisions, another probable motivating factor was a desire to assuage their other, non-political, advertisers’ concerns over brand safety during the election season. For instance, while Facebook receives a large share of political digital ad spend dollars, this money remains a small fraction of its overall advertising revenues.

Facebook is a major player in the social media space, seen as a forum many citizens turn to as a place to express their views and connect with like-minded others, and founder Mark Zuckerberg is known for advocating for speech with limited restriction. At the same time, the company’s revenues come from its position as one of the two major ad platforms in the digital advertising space. These two missions naturally set up a tension inherent between the desire to be a forum for speech and a place that needs to help brands protect their image.

Companies Pull Digital Advertising Campaigns During 2020 Political Cycle

Indeed, more than 1,100 companies pulled their advertising from the platform during the summer over concerns that the company did not do enough to combat hate speech on the site. Snap, the parent company of messaging app SnapChat, credits this boycott with a 52% increase in their revenues during the third quarter of 2020.7 Incidentally, SnapChat takes a relatively stronger line on political advertising than does Facebook, explicitly disallowing misleading or deceptive ads, and also providing an archive of political ads along with the audiences targeted.

For those looking to understand more about social media political advertising, Facebook’s Ad Library, while not perfect, does provide one of the best looks at political advertising, given Facebook’s continued dominance in this space. The Illuminating Project at Syracuse University has compiled the Ad Library data around the 2020 presidential election into an accessible format. Using their dashboard, we can easily see for instance that between June 1 and Oct. 26, 2020, ads targeting Texas voters bought by the 20+ Facebook pages officially associated with the Trump campaign. As a result, this yielded 298 million impressions, or distinct on-screen appearances, compared to the Biden campaign’s 11 pages’ ad reach of 93.2 million impressions targeted to Texas voters. Overall, the Trump campaign paid an average of $23 per 1,000 impressions to reach Texas voters compared to the Biden campaign’s $28/1,000 impressions.

Impressions v. Reach

It should be noted that impressions are not the same as reach – the number of people who actually look at an ad – however, and Facebook does not share this information. Additionally, some prefer to look at engagement – likes, reactions, shares, and comments – as a measure of social media success. Despite some of his stated concerns of being silenced on social media, data from prior to the election showed that President Trump’s campaign received more impressions and achieved significantly greater engagement on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube in the final months of the campaign season than did the Biden campaign.8

The intersections among business needs, brand safety, advertising trends, and free speech and citizenship that we see illustrated in election advertising are complex, requiring critical thinking and strategic planning to meet business objectives. In the PVECOB, students can explore these issues and more in courses such as Emerging Media in Advertising and Emerging Media Law to prepare themselves to be effective business leaders.

1 https://digiday.com/marketing/ahead-of-the-ana-conference-marketers-take-stock-of-coronavirus-induced-changes-to-consumer-behavior/

2 https://campaignlegal.org/update/long-wait-updated-fec-rules-internet-ad-disclaimers

3 https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/08/trump-biden-pacs-spend-big-on-facebook-as-election-nears.html

4 https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/01/americans-main-sources-for-political-news-vary-by-party-and-age/

5 https://www.justice.gov/file/1035477/download

6 https://about.fb.com/news/2020/09/additional-steps-to-protect-the-us-elections/

7 https://www.ft.com/content/cb762955-10bb-4d1e-bfb3-87c4ecf9d915

8 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/22/technology/trump-facebook.html?