Education as Public Good

The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights makes the case, among other things, for compulsory education in the interest of social web-being. Although the United States is a signatory to this 1966 UN treaty, it has not been ratified. However, compulsory education has provisions in several layers of federal, state, and local law in the United States. Although not directly addressed in the United States Constitution, the rights to education are provided in both the General Welfare and Commerce clauses of the federal constitution, as well as in several amendments (First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth).

The General Welfare clause is of interest as it affords that “the United States Congress the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excides to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and welfare of the United States… (found in Article I, § 8, cl. 1).” The basis for federal involvement in education largely stems from this clause. Case law argued before the United States Supreme Court, Gibbons vs Ogden in 1824, has established, in a manner consistent with the doctrine of stare decisis, that commerce may be understood in a broader context to include “… advancement of society, labor, transportation, intelligence, care, and various mediums of exchange (Chief Justice Marshall, 1824).”

Lunenburg (2012) commensurately asserts that this legal precedent establishes “…literacy as a necessity, and a right, of every human being. In this broad context, the constitutional assertion of education and knowledge as an aspect of commerce is vital to the growth and prosperity of the nation.“

The Knowledge Machine

The basics of education can be understood from a classic adage concerning the three R’s: “reading, writing, and arithmetic.” In 1993, Seymour Papert, writing for Wired Magazine, presciently questioned these components in a reflection on what information communication and computing technologies would soon bring to the world. Seymour alludes to how advanced in computing would bring about a “Knowledge Machine.”

This would transform and transcend common modes of learning such that the extant education system would either “… change radically or collapse.” What Papert was likely alluding to was the inevitable onset of the World Wide Web as a primary use of the Internet for the purposes of informing, entertaining, and participation in broad swathes of daily life. Papert’s conceit was that unfettered exploration would triumph over the mediated acquisition of compulsory education.

With the ubiquity and pervasiveness of computing now realized through a plethora of personal computing devices that bring information and services to you (mobile devices being the prominent example), it is arguable that Papert’s 1993 vision is realized. To wit, the COVID-19 pandemic presented a world-wide experiment in moving education to a virtual and “online” space, for better or worse. I can relate to some of these sentiments as I often will say the following to students after asking questions of fact: “the knowledge and wisdom of the ages is available to you at your finger tips… go ahead and Google it.”

The Oracle of our Age

That a product becomes so associated with the market it engages so as to become a generic term, as noun or verb, for the utility of the product, then that product is emblematic of the value and utility of that category of product. Thus, we become perfectly accustomed to suggesting that somebody utilize a Web search engine to obtain relevant results by “Googling it.” Just five years after Seymour Papert’s Wired Magazine article, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, students at Stanford University, developed the earliest algorithms that have lead to the market dominance in Internet search.

To put things in perspective, Google (parent company was renamed as “Alphabet” not too long ago), held a 92.48% market share of search engines in May 2022. Thus, when you hear people talk about Search Engine Optimization so as to more prominently place their websites for discovery, this primarily equates to Google optimization. The implications here are curious to put it lightly, and perhaps akin to Seymour’s Knowledge Machine. However, it is difficult to determine if Seymour anticipated a monolithic Goliath.

It’s in the Clouds

Inevitably, and accelerated by mobile computing, the Seymour’s “Knowledge Machine” is so pervasive and ubiquitous that we now refer to the plethora of sources and sinks of information available via the Internet as “the Cloud.” To be enveloped with the cloud is to have available answers, facts, and intrigues available on-demand. However, lest we become the Buy-n-Large-sponsored intrepid sojourners of the starship Axiom, from the 2008 Disney/PIXAR film “WALL-E,” some pause for reflection is the central argument of this post.

As I’ve posted here previously, machine learning and artificial intelligence are largely algorithmic endeavors of a principally deterministic nature. Although ever more capable of divining useful patterns from stochasticity, the algorithm has not demonstrated full human equivalence.

What Makes Us So Special?

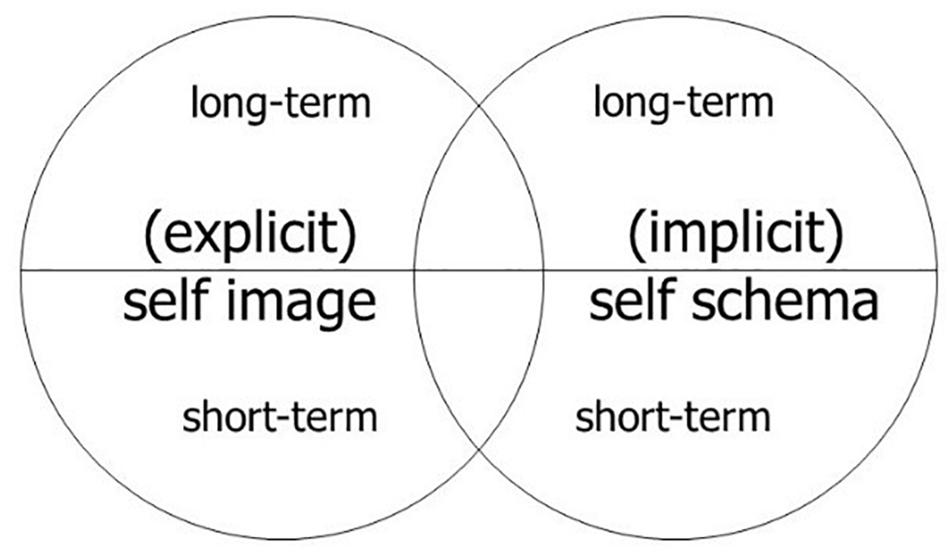

Higher Education provides a reasonable backdrop from which reflection may proceed. As a premise, higher education allows for a blend of arts and sciences that explore questions of ontological and epistemological nature. What is, why, how, and by what means. Eventually, values are attached to these questions and a mark of higher education is to allow for critical discovery, comprehension, and sense making. These are all matters of self and how you relate to the world and other people. As such, as Albert Newen alludes to in graphic above, we develop a concept and model of self that is shaped and reshaped by experience and reflection.

Have A Taxonomy

In what Argyris and Schön have identified as “double-loop learning.” an education extends past fact-acquisition and into question formulation, problem setting, and problem solving. In higher education, we commonly utilize the thinking manifest in Benjamin Samuel Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives as a means of classifying and identifying the progression of learning that culminates in the ability to produce new or original work.

Stops along the way in Bloom’s Taxonomy include evaluation (justify and argue a position), analyze (draw connections among ideas), and apply (use information in new situations). This is not to imply that higher education exclusively holds the keys to unlocking this progression, but rather than higher education is a manifestation of our abilities as a species such that we can conceive of, create, and support such affordances that lead to our own development and growth.

What Makes Us So Vulnerable?

As humans, our advanced sensory array, coupled with our advanced cognitive capacity, had undoubtedly driven our position as an advanced species. In his book, The Master and His Emissary, Ian McGilchrist explores the psychology, philosophy, and neuroscience that explores the divided brain – our analytic and aesthetic proclivities. Put simply, our mind and intellect, coupled with our emotional dimension, is simultaneously our source of strength and weakness.

What of This Allegory?

As a literary device akin to metaphor, which is an essential component of comprehension according to McGilchrist, an allegory provides us with an illustration or story that provides, or suggests, a lesson related to value or principle. So as to sum up the value of education, the poignant accomplishment that is higher education, and Seymour’s Knowledge Machine, let us explore Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Rather than transliterate this for you, I will present an extrapolation and appropriation of Plato’s Allegory of the Case.

What if you’ve become accustomed to single sources and modes of knowledge without recourse for your own discovery. What does law related to the common good have to say about monopolies? And what are the gifts we possess to the common travails of logical fallacies described by Sir Francis Bacon as Idola Specus (prejudices), Idola Tribus (human nature), Idola Fori (language, meaning, and semantics), and Idola Theatri (philosophies and false notions). Each of these are endemic to the human condition. However, the question is your ability to appraise and appreciate these from within, and without, daily comprehension.

Back To The Internet

Returning to the Internet, the World Wide Web, Mobile Computing, and Social Media, all are marvels of opportunity, possibility, and discovery. However, we must take care not to become “hoist by our own petard.” Take note and care that the Knowledge Machines that dominate dissemination, discovery, and digestion of knowledge are both mediated and moderated by computer algorithms that are owned and operated by monopolies that have yet to be meaningfully regulated by the anti-trust laws that have been developed to assure common good and welfare.

None of this has been articulated to call for the end of Google, or YouTube, or Facebook, or any of the modern pillars of informing and discovery. However, it is telling that Elon Musk was given pause by the process of separating wheat from chaff in the case of Twitter and his endeavor to acquire that company. The sticking point for Elon Musk is a fair question: just how many accounts are real and how many are “bots” constituting non-human actors whose goal-seeking algorithm is not likely fully known? The concluding advice here isn’t particularly novel: Caveat Emptor. Basically, while you can’t control the Internet, you can control your behavior in and around it.

The promise of Seymour Papert’s “Knowledge Machine” is here and in our midst: Use precaution when operating such heavy machinery.