As innovations diffuse, their long-term mark on the fabric of daily life. While they are not immutable, they become commonplace and “normal.” In our physical space, cities around the world are shaped by the use of automobiles. Supplanting the horse as motive power, the landscape changed in the 100 years after the introduction of the Ford Model T is profound.

This is not to say that the Model T was the first automobile, but Henry Ford’s mass production led to both commodification and proliferation. These forces continued to shape urban, suburban, and even rural landscapes around the world to some degree. In this example, the inflection point, was vision and leadership on the part of a motivated individual: Henry Ford.

This thought experiment can be repeatedly extrapolated: electricity, batteries, radio and wireless communication, and, finally, the integrated circuit.

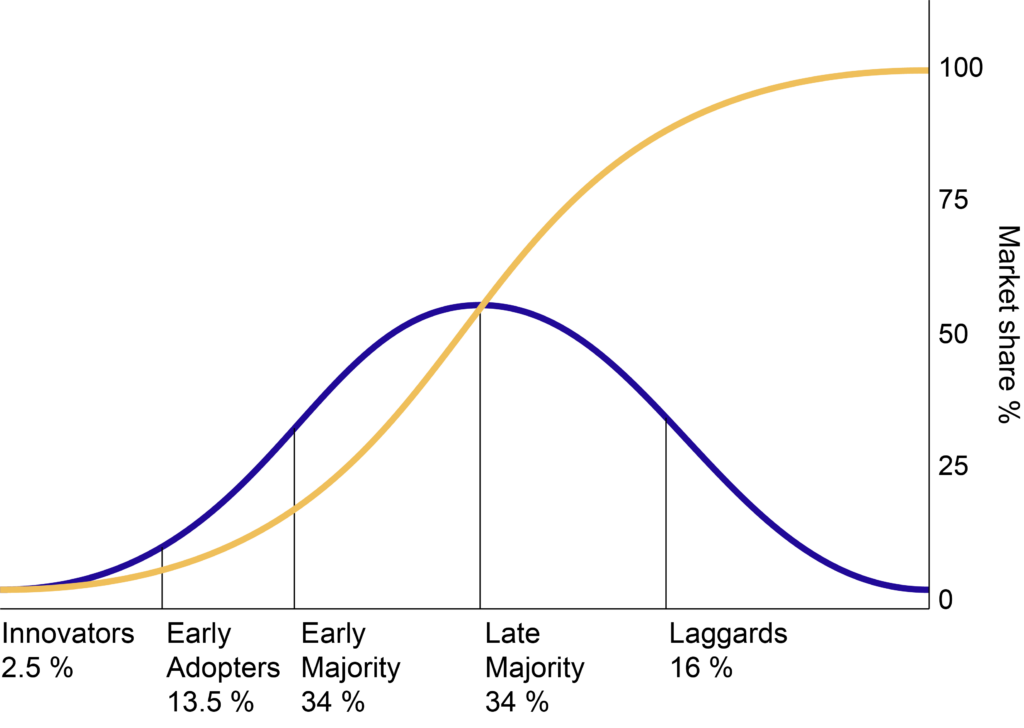

Innovators are Leaders

While it is important to recognize and honor inventors, innovators are not always the originating inventor. They are more often the leader willing to push an invention through the initial stages of innovation diffusion. As a recap, Everett Rogers is credited with the introduction of diffusion of innovation as a theory. From this theory we use terms such as “innovators” and “early adopters.”

IT is All Around You

Earlier, I used the transformation of automobiles from craft to industry as example of a diffused innovation that has remarkably and unmistakably changed the world. It could be argued that the availability and ubiquity of personal computing has also unmistakably changed the world.

The impact of this innovation is ongoing. It is the “personal” component of computing. This computing is where you are and responsive to the context of your life in the moment. It has truly reshaped the world. We use terms like “Big Data” now to describe the effluent of our constant transactions with our information environment. Computing is literally on and about our persons for the duration of our waking hours.

Confluence and Convergence

An innovation is particularly powerful when it conjoins with other sympathetic innovations such that, synergistically, they work in concert to accelerate transformation. In the case of “personal” computing, we can focus on three leaders and innovators. Their leadership transformed and facilitated the personal computing I refer to here.

Of note, I am not talking about the desktop PC in your home or work office. I am speaking of the computers we hold in our hands, that we interact with in our cars, and other network-enabled devices. These work together to seamlessly connect us to our information environment and the societies and cultures we engage in with those devices.

This does not exclude the PC, but broadens the available devices as a collection of access points to your broader information ecosystem that is build around you.

The Power of the Cloud

Many can be credited with bringing us “The Cloud.” The term simply refers to the use of the Internet and World Wide Web to host various networked applications. These work together to provide common access to resources regardless of where and how you access the network.

Consider services from Google such as Gmail or Google Docs as examples. While there are many giants whose shoulders these innovations stand upon, I choose to focus on Linus Torvalds. The free and open source Linux operating system bears his namesake.

As a young computer science student, Linus steadfastly committed himself to the emerging notion of making a Unix operating system that was open to all. The whose source code of this could be freely modified and redistributed.

The “U” in Unix alludes to the fact that, in the early days of computing, machines and their operating systems were crafted uniquely for each other. They had not yet transformed to the standardization that would poise computing for ubiquity. There was both a tenacity and audacity to Linus’ approach such. Now let’s skip forward 20 to 30 years. The overwhelming majority of operating systems that power the technologies that make the “Cloud” possible are derivative of the Linux operating system.

So, the actual hardware and software implementation of facilities that make your “Cloud” experience possible rely on Linus Torvalds leadership. As a study in leadership, Linus was not a powerful CEO in the executive suite, he was a student taking advantage of the Internet itself to proliferate his ideas and his technical contributions.

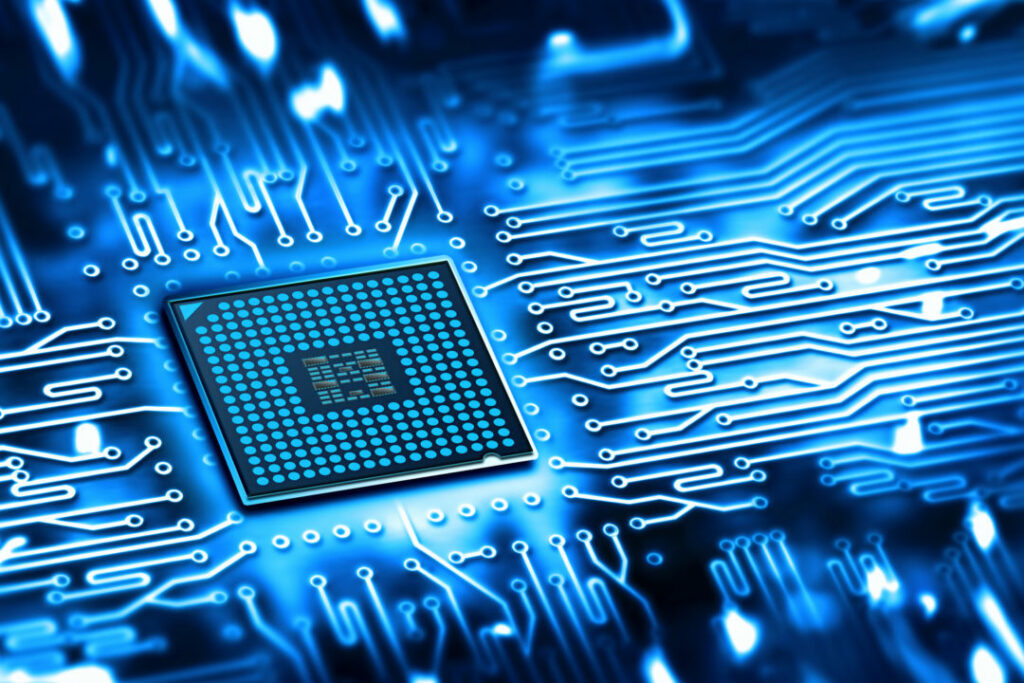

The Power of the Chip

Microchips, a series of integrated circuits arranged on silicon substrate. They were designed with an architecture that provides the basic operations of a computer. Technological advances have consistently optimized and increased the density, thereby shrinking the space and resources needed required for computing operation.

Innovations in microchips stretch back to the post WW2 period. But it would be the hobbyists and tinkerers, working on personal computer “kits,” who set progress in motion. They would popularize the notion that a computer could be an item in the home, available to normal folks, and otherwise a normal idea.

Examples include Ed Roberts and Forrest Mims, who formed Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems. From a garage in Albuquerque, New Mexico in the 1970s, they perfected the process of selling home computer kits.

It would then seem no accident then that Bill Gates later started Microsoft there, or that Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak emulated the “sell computer kits from a garage” model as the beginning of Apple. These are not studies in chip innovation. No, they are studies in transforming cultural uptake of an innovation such that markets are transformed.

In the decades since these early steps, whilst MITS did not survive, those that emulated the elements of model – Microsoft and Apple – progressed to profound domination of personal computing.

The Power of Mobility

The personal computer proliferated as a device that you sat in front of, with screen, keyboard, and mouse. But the need to present yourself to the machine is somewhat incongruent and makes the “personal” moniker somewhat of a misnomer.

The last piece of the “Triple Crown” of our contemporary computing landscape is mobility. Whereas both laptops and personal data assistants (PDA) had evolved as personal computing evolved, each had some drawbacks. Whilst smaller, the laptop still required a human-computer interface that relies on keyboards and pointing devices.

PDAs were designed to fit in your hand, they did not yet have sufficient power or, more importantly, high-speed network access. Here we focus on two leaders. Steve Jobs, starting with the iPod/iTunes combo, normalized the personalization of music. The iPod provided both a digital marketplace for music and a device to consume that digital resource.

Sure, perhaps the Sony Walkman let us listen to music on the go, but it did not profoundly connect to a digital ecosystem. Another leader, Stan Sigman from Cingular and AT&T, partnered Steve Jobs to effect. In the spirit of Roger’s Diffusion of Innovations theory, generate the market, for the mobility we know today: a mobility of convergence.

The fruit of Job’s and Sigman’s partnership constitutes a study in convergence: computing power, on-device sensors, high-speed network accessibility, and hand-held form factor. The human-computer interface design had significantly improved to accommodate device use in the context of daily life.

Chicken or Egg?

The journey of illustration I have attempted here is to pose the question: what matters more, the invention or innovation?

The examples of innovation shared here suggest that certain individuals played pivotal roles. They understood the invention. They possessed enough imagination, leadership, tenacy, and audacity to execute on this vision. These were necessary for Roger’s theory of innovation diffusion to function.

Which is the chicken and egg? The egg, the actually invention, was always necessary. Many years of computing and operating system design existed prior to Torvalds’ work. But Torvald carried a derivative instantiation forward and drove the innovation.

Early pioneers of home computing kits didn’t event the parts they used, but conceived of an idea that was sticky enough to inspire other leaders. Neither Steve Jobs nor Stan Sigman necessarily invented the components of the iPhone and the iPhone ecosystem. But they possessed the leadership qualities to move a vision forward and develop a market.

On the subject of mobile computing and the cloud, these innovations have remarkably changed the world.