A couple years ago on an enchanting summer afternoon in Seattle, my family and I went to a park to enjoy the weather. We were not surprised to find that many other families also sought to bask in the sublime sunshine. After all, there is not a locale more beautiful than Seattle in the summertime. Amid the crowd, my six-year-old son was quick to make friends with a couple of kids about his same age. What came next was a lesson on cancel culture that was as meaningful to me as it was subtle.

Later on, I heard the children get into a disagreement which escalated. It didn’t seem like the children could agree on what the rules of their imaginary game should be. One of the kids got upset and went to her parents, who were sitting on a bench nearby. I decided to eavesdrop and not make it known that I was the “other parent.” After hearing their daughter’s complaint, the parents said, “It’s ok. You don’t have to get along with everyone. Go find someone else to play with instead.”

The parents’ response immediately surprised me and left me feeling sad. I told myself how silly it was to get emotional about such a trivial event. I mean, they were just young kids playing together at a park, right? But the sadness stuck with me for a long time, and it took me a while to figure out why.

Teaching the Next Generation How to Cancel Someone

Upon further reflection, I realized why this exchange bothered me so much. The parents’ counsel reflected our current cancel culture, whereby individuals cut ties with someone who says something objectionable or offensive. Yes, we should hold people accountable when they make inappropriate remarks (both online and offline). But with an extreme “cancel culture” attitude, there is no opportunity for discussion, discourse, common ground, or understanding. Many people think that “cancel culture” has gone too far to the point where it is crippling our society.

Today, we tend to cancel celebrity types by publicly shaming them online and removing them from our social network. However, people cancel others via non-virtual means, and cancel non-famous people in their local communities. In my situation, the parents at the park were essentially counseling their daughter to “cancel” my son and go find someone else whom she would better get along with. Wouldn’t it have been better if the parents had coached their child on how to get along with my son? Or how to resolve the petty conflict rather than simply avoiding it? What a missed opportunity for effective parenting! The girl is going to subsequently lean toward canceling during myriad future moments of conflict later on in her life.

How Did We Create Our Cancel Culture?

How did we arrive at our current cancel culture? One explanation involves our method for how we consume media and content. Social media algorithms tailor our news feeds and we “shop” at polarized news outlets. This leaves us in a situation where it is becoming increasingly uncommon to encounter someone who thinks and acts differently. As a result, when we do have such an encounter, we think the other person must be from Mars due to how different their worldview is. And who wants to compromise and give up something they value for the sake of a Martian? It is much easier to just cancel the Martian and instead find an earthling to talk to who shares your viewpoint.

Another explanation for our cancel culture focuses on the lack of accountability inherent in socially interacting online. People say and do things they would never say and do if they were together in person. Sometimes this is because of the anonymous nature of online platforms. But other times it is because in the virtual world we are less attuned to social cues that would warn us that what we’re about to say or do is inappropriate and offensive.

Although these explanations make sense, they are both rather contemporary and do not reconcile the fact that history shows that people have been canceling/ostracizing/excluding others since the dawn of time, even if it looks different now with computers and screens.

Cancel Consequences

There are undoubtedly many negative consequences stemming from our current cancel culture at the societal level. It scares me to think of individuals behaving the way they do online towards those in their “real life.” Yes, people adjust their behavior and do not act the same way in person as online. But it is naïve to think that there is zero cross-influence among the domains.

Individuals aren’t going to be successful if they start “canceling” anyone who disagrees with them in their “real” communities. How far will an employee get in their career if they cancel coworkers or customers with different views without giving others sufficient space to explain themselves? (This happens, as evidenced by accounts of employees who are fired for their mistaken views posted online.) It is almost inevitable for one to work amongst others who maintain alternative views or who disagree. Similarly, how happy will an individual be in their relationships when the individual just “cancels” their friends and family in response to offensive remarks or moderate disagreements? It is not a stretch to think that a “cancel attitude” is contributing to our epidemic of loneliness.

Cancel Culture Is Not New, It Just Looks Different Now

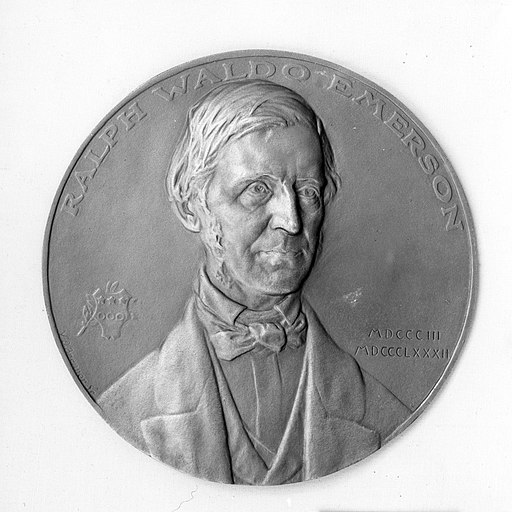

I recently came across these themes while reading Ralph Waldo Emerson. Over 150 years ago, Emerson penned the idea that others deserve our attention rather than our cancelation: “Let us treat men and women well; treat them as if they were real; perhaps they are,” and “do broad justice where we are, by whomsoever we deal with, accepting our actual companions and circumstances.” I find it intriguing how Emerson chooses to emphasize how others are “real”—not something you would expect pre-Hollywood, pre-virtual reality, pre-curated social media profiles. I also like his counsel that we should not neglect those close to us in our immediate proximity. Wouldn’t this be obvious to anyone in the mid-19th century who wasn’t distracted by a virtual world? Apparently not. It would seem that these themes of cancelation have been with us for quite some time.

I emphasize evidence of cancel culture not being new because I think the solution is the same one we have been using for centuries. Instead of canceling others, let us seek to understand them. Instead of avoiding conflict (which paradoxically leads to greater conflict later on), let us resolve conflict so that we can live in greater harmony among those with different views. Let us be “real” in our interactions and take ownership of our communities and situations. And finally, let us teach our children the correct way to behave, even (or especially) during common playground interactions.

Dr. Trevor Watkins

Assistant Professor of Management & Foust Professor of Business