I would like to make the case that paying employees low wages is akin to giving children coal for Christmas. Let’s first consider the holiday “tradition” of naughty children receiving coal in their stockings.

A traditional folklore storyline known by even those who do not celebrate Christmas is that naughty children risk receiving a lump of coal from Santa instead of nice gifts. This aspect of Santa’s agenda was not in the original story. Rather, the story evolved to include coal at the turn of the 20th century when coal became a staple in homes. Over time, millions of American families have adopted the coal aspect of the Santa story as a way to encourage good behavior in their children.

But why does the coal component of the story persist so strongly in American culture? We have evolved past the point of piling up coal by our fireplaces, right?

Perhaps because it feels right to tie children’s behavior to rewards and punishments. Reminding children of the consequences of their actions avoids entitlement issues. The looming threat of coal also avoids sending the wrong message of getting things that aren’t deserved (why should naughty children receive good gifts?). And perhaps because our larger meritocratic and capitalistic culture influences parents to reinforce the value of merit.

Coal is an Empty Threat

Despite myriad threats of coal for bad behavior, it is very rare to hear of children receiving coal. And when children do receive coal, it is usually done in jest. In other words, even misbehaving children end up getting at least a few modest gifts for Christmas.

But doesn’t giving naughty children good gifts violate the core tenets of meritocracy and capitalism? Aren’t we facing the risk of breeding entitlement in our children by giving gifts when they don’t deserve it? Perhaps, but we don’t seem to stress this point.

Why? Because children deserve a reasonable number of unconditional tokens of care from their parents. Because children are entitled to a reasonable number of signals that instill in them a sense of security and stability. And really, it is inhumane to give children a dirty rock as a gift. Hence, in this case, the “care” value outweighs the “merit” value to the point where parents who would endorse merit over care by literally gifting children coal would likely be reported to state agencies.

The Holidays in 2021: The Great Resignation

We are now experiencing the “Great Resignation,” in which unprecedented amounts of employees are quitting their jobs. As one sample statistic, September 2021 marked a record-breaking month of 4.4 million Americans quitting their jobs. This Great Resignation is attributed mostly to the economic and lifestyle effects of COVID. My colleague Dr. Anthony Klotz, a researcher at Texas A&M who studies employee departures, suggests that COVID has led to “pandemic epiphanies.” People have essentially woken up and realized that they want to do other things with their life.

Low Wage Earners Are the First to Leave

Importantly, entry level workers experience these epiphanies to a greater extent. Lower skilled employees are abandoning their positions the fastest. These jobs pay low wages, while oftentimes not being any less demanding than their higher paying counterparts. This point suggests that these epiphanies are fueled more by, “this stinks and it isn’t worth it,” than it is by “it’s a great job, but I just found something even better outside of work.”

As a result of the Great Resignation, many businesses can’t hire enough employees to adequately run operations. This has myriad negative consequences ranging from stores closing their doors permanently, to restaurant patrons experiencing longer wait times, to travelers experiencing multiple flight delays or cancellations. Stated differently, the Great Resignation negatively impacts everyone, regardless of their job.

In response, many organizations are offering hiring bonuses and raising their wages like they never have before. I just pulled up a job posting for a McDonalds Crew Member that stated they are offering a signing bonus of up to $1,000 based on availability and experience. Wow!

The Inhumanity of Low Wages

But doesn’t increasing low wages (e.g., minimum wage) violate the core tenets of meritocracy and capitalism? Aren’t we facing the risk of breeding entitlement in our employees by giving higher wages when they “don’t deserve it”? Perhaps. But I don’t think we should stress these points.

Why? Because employees deserve a reasonable number of unconditional tokens of care from their employers. Because employees are entitled to a reasonable number of signals that instill in them a sense of security and stability. And really, it is inhumane to give employees an unlivable wage as their payment (while basking in one’s own six, seven, or even eight-figure salary). Hence, in this case, the “care” value outweighs the “merit” value to the point where managers who would endorse merit over care by literally paying employees an unlivable wage would likely be reported…as places where employees walk off the job and don’t come back.

Is it brazen of me to liken giving employees low wages to giving children coal? For my analogy to ring true, there must be a defense that low wages (e.g., the current minimum wage of $7.25 per hour) are 1) not livable wages, and 2) are voluntarily set by managers (it really is their choice to “give” the wages).

1: Is Our Minimum Wage Unlivable?

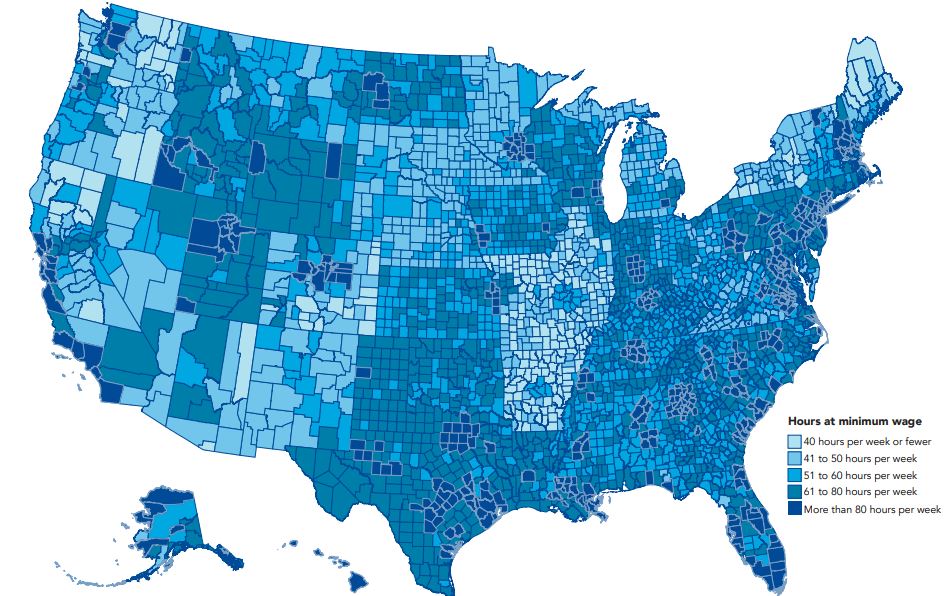

The above image of the US depicts the number of hours a minimum wage earner needs to work in order to afford a modest one-bedroom rental. As the shades depict, there are very few places where a minimum wage job will be sufficient to afford the cheapest of all rentals. Consider also the following facts from a recent report furnished by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC):

- In 49 states (!), the average renter earns less than the average two-bedroom housing wage. This means that half of those who rent cannot afford to live in a two-bedroom place. It also means that this problem persists in places beyond just San Francisco.

- The average renter must work 53 hours a week to afford a modest two-bedroom apartment without becoming housing burdened. This equates to thirteen hours of overtime just to afford a modest apartment!

- In Texas, a minimum wage earner would have to work 121 hours a week to live in a two-bedroom rental and avoid becoming housing burdened.

- The college education pay premium increased between 1979 and 2019. Meanwhile, median wages for those without college degrees—those who are at the mercy of low wages—went down. This means that while wages have gone up the last few decades in general, theoretically assuaging the hurt of increased cost of living, they haven’t gone up for the poorest among us, putting those earning low wages further in the hole.

2: Can We Afford to Pay Low Wage Workers More?

I firmly believe we can afford to pay low wage workers more. There is strong evidence in support of my conviction. The same NLIHC report states that during the same period of 1979 to 2019 when median wages fell for those without degrees, economic productivity rose by 70 percent. Apparently, none of the benefits of this added productivity have gone to the front-line workers.

So where have the benefits gone? One clear place is the C Suite. For example, CEO compensation has grown by 940% since 1978 (oh, and this is inflation-adjusted). Excessive CEO compensation is fully volitional, yet unnecessary (presuming you believe that “keeping up with the Joneses” is an unnecessary game). But when paying executives large sums of money impedes organizations in being able to pay front line workers a livable wage, it goes beyond unnecessary and becomes unethical.

Costco Leading the Way

There are stellar organizations who are leading the way on paying lower skilled workers more—sometimes at the expense of leaders’ salaries (but don’t panic, the leaders are still at the 99th percentile in income). Consider Costco, who raised their minimum wage to $17 this year. ($17 an hour for pushing grocery carts?!?). Far from crippling their company, this “higher pay” practice has allowed them to maintain industry leader status for decades. One clear upside is that such practices reduce the turnover rate, which typically imposes steep costs on organizations. Costco’s turnover rate for those with at least a year of experience is less than six percent! That’s unheard of for a retail operation!

Smaller Companies Can Also Lead Out

Even small companies without the deeper pockets find that increasing low wages for entry level workers pays off. Consider the beacon company Gravity Payments, the credit card processing company who raised their minimum salary to $70,000 in 2015. This is a company with just 120 employees. Yet they increased their low wage earners’ salaries by double in some cases. To make this move, CEO Dan Price took a million dollar pay cut himself, also reducing his salary to $70,000. (Which underscores the point that executive compensation is unnecessary).

Since making this move six years ago, Gravity Payments has received over 30,000 resumes for their 50 new positions. And their turnover rate has been substantially more favorable ever since. During COVID, they completely avoided layoffs. Moreover, raising low wages has elicited fierce loyalty. Indeed, employees volunteered to take a pay cut during the pandemic to help keep the ship afloat. This level of loyalty hardly exists today (although we might find it at Costco).

Conclusion

In sum, there is ample evidence showing that our workers’ low wages are unlivable, and that we can afford to pay them more—but simply choose not to. The COVID pandemic has led to epiphanies for many of these low wage earners, who have been suffering for years. Low wage employees are finally done putting up with the disrespect. These employees are rejecting the gift-wrapped coal, and are justifiably asking for the livable wage they deserve.

How much longer are excessively high-paid organizational leaders going to turn a blind eye to their moral obligation to respectfully provide entry level workers a dignified wage? How much longer will they rely on the shallow “they don’t deserve it” merit-based logic as an excuse? By my estimation, they won’t be able to do this for too much longer. Luckily, market forces are starting to push them to pay more—something they should have proactively chosen to do a long time ago.