Economists love to talk about money. Everywhere you look, you see economists in news columns or on television chiming in. They offer projections about the flow and transfer of money between people and institutions, such as banks, countries, or the stock market.

Macroeconomists love to talk about a concept called gross domestic product (GDP). This is a measure of the total value of goods and services produced within an economy. According to the latest reports of the Federal Reserve , the growth in real US GDP is projected to rise substantially this year. The economy is slowly recovering from the COVID-19 crisis.

Money makes the world go round

Where did this obsession with money come from? Do economists assume the only thing normal people care about is the number in their bank accounts?

What about the things that truly make us happy? Things like taking vacations with our family, and having a clean and safe place to live? Or what about having the resources to pursue our personal hobbies? It turns out, as weird as they may seem sometimes, economists are well aware attuned to the finer things in life.

A key tenet of modern economic theory is that government policies should aim to maximize the utility of its citizens. The notion of utility, which is simply a fancy way of saying “happiness,” harks back to John Stuart Mill’s utilitarian moral philosophy. It has been rooted in economic thought since Daniel Burnoulli formalized it through what is known as a utility function.

In short, economists realize that money is simply a means to an end. The real value of money comes not from having money in itself, but rather the new opportunities people have to increase their happiness as they become wealthier.

What is “happiness,” exactly?

But two questions immediately arise when one considers this utilitarian approach. The first question is based on the assumption that money is only a means to the end goal of making us happier. So why don’t we simply make life easier by directly measuring happiness to begin with?

The main problem with this is that getting a reliable measure of even one individual’s “amount of happiness.” It’s a very difficult task, let alone measuring the happiness of a country. Happiness has sort of a subjective quality about it. Consequently, it is much more difficult to accurately account for than, say, keeping track of a country’s GDP.

This difficulty, however, has not deterred everyone. Take, for example, the Journal of Happiness Studies. This highly-regarded, peer-reviewed economics journal publishes studies that seek to make the study of happiness a more tractable science.

In fact, the country of Bhutan keeps track of a measure of gross national happiness (GNH), which their former king declared to be of more national importance than GDP. Still, because of the measurement difficulties mentioned above, such approaches have yet to catch on in the wider economic world.

Can money buy happiness?

The second question which arises is whether money or wealth truly is a good, albeit indirect, way to measure an individual’s or country’s happiness. At first glance, it would seem that making this assumption is on good logical footing. Surely giving me more money shouldn’t make me less happy? Right?

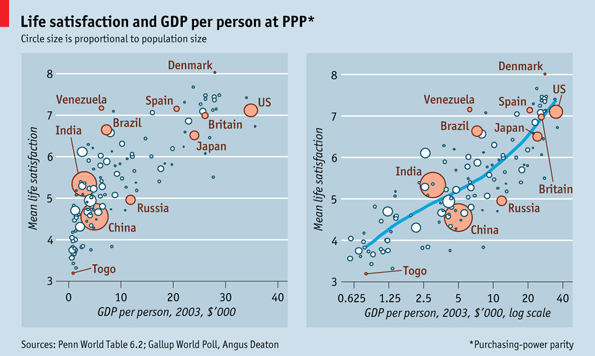

Unfortunately, this seems to be as far as we can get without any data. But we’re in luck. Because part of the study of happiness which I mentioned above is concerned with determining the relationship between wealth and happiness. Such studies have produced charts similar to the ones below:

One the left-hand side we see a plot of a large collection of countries. GDP per person (income per person) is on the bottom axis, and a measure of happiness is on the vertical axis. On the right-hand side we see the same plot with a trend line added in. This roughly tells us the statistically justified best way to think about the relationship between these two variables.

And the correlation is…

In essence, we see that happiness or life satisfaction is strongly and positively correlated with wealth. The relationship is obviously not perfect, though. For instance, we see that Denmark is both slightly less wealthy but at the same time slightly more happy than the US.

The same anomaly holds on a much larger scale when we compare Britain and Venezuela. Perhaps an explanation is that after some point, accruing a little more wealth comes at the cost of a lot more work. The result is a lot less time for leisure.

Nevertheless, despite these outliers, the data tell a compelling story: Measuring wealth is a good, albeit indirect and imperfect, indicator of happiness, and it’s pretty easy to measure.

If you would like to learn more about this relationship, consider taking my Econ 2302 course in which we discuss such topics in more depth.

Eric Hoffmann

Assistant and Pickens Professor of Economics

References

- https://econreview.berkeley.edu/beyond-gdp-economics-and-happiness/