The last few months of every year are full of holiday traditions. From Halloween trick-or-treating to staying up until midnight to ring in the new year, we all have our favorite holiday rituals. While I am personally fond of eggnog and Christmas music, the end of the year also reminds me of a longstanding debate among finance professionals and researchers: The January Effect. In this post, I will give a brief overview of the January effect as well as some of the hypotheses for why it exists.

The January effect is the observation that stocks have abnormally high returns in January. While the exact mechanisms for its existence are still under debate, one popular hypothesis is that markets are rebounding in January after a high volume of tax-loss selling in December. That is, investors will often sell poorly performing stocks at a loss before year-end to reduce their tax burden since capital losses are tax deductible. The high volume of sales just before year-end drive prices down, creating potential for a rebound in the new year. Another potential explanation is that people use holiday bonuses to buy stocks in the new year, creating upward pressure on stock prices.

What does the data say?

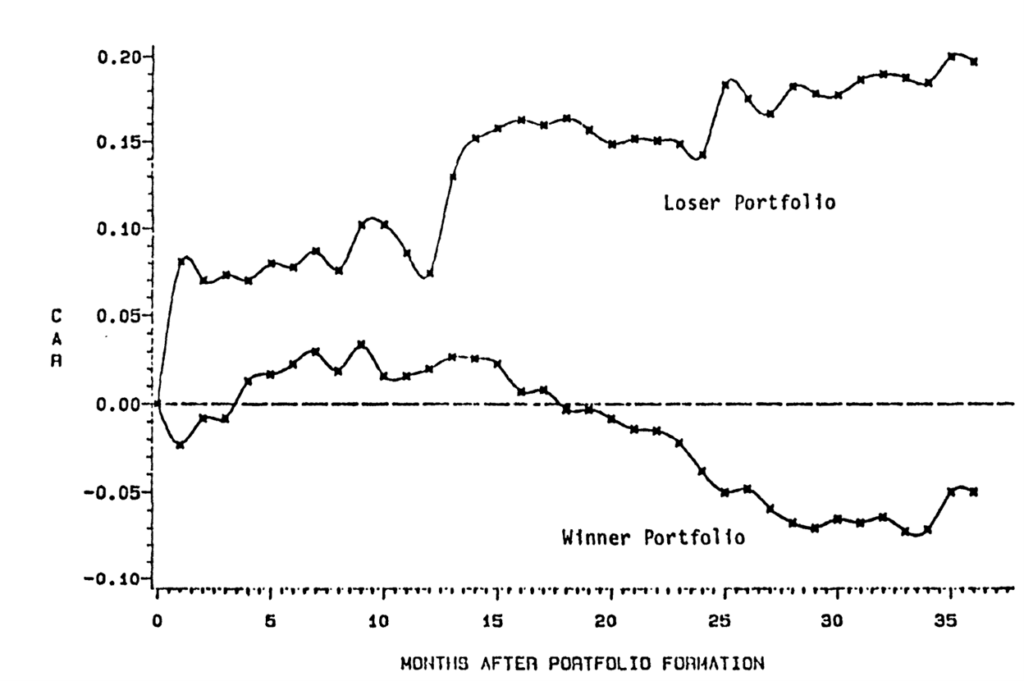

Whatever the mechanism, data analysis seems to show that the January effect is real. For example, De Bondt and Thaler (1985) create a portfolios of “winner” stocks that have done well over the last 3 years and a portfolio of “losers” that have done poorly over the same time period to see if one portfolio outperforms the other. In addition to showing that the loser portfolio outperforms the winner portfolio, they also show that the loser portfolio has abnormally high returns every January. Figure 1 shows each portfolio’s return in the 36 months after the winner and loser portfolio are formed with months 1, 13, and 25 representing the month of January. Each of these months correspond to large increases in stock returns relative to the other months considered suggesting that stocks earn higher returns in the month of January.

Should You Trade on the January Effect?

Now that you know about the January effect, it may be tempting to buy a bunch of stock after the holiday break. However, it is not quite that simple. Researchers have shown that there is more to the story than simply, “all stock prices increase throughout January.” Donald Keim of The University of Pennsylvania published a study in 1983 suggesting the January effect was only evident in small stocks.

Furthermore, a 2012 article by Richard Sias of The University of Arizona and Laura Starks of The University of Texas at Austin find that the January effect is stronger for stocks that are more favored by individual investors relative to stocks favored by institutional investors (e.g., hedge funds, mutual funds, and pension funds).

These studies suggest that abnormally high returns in January may be concentrated in a subset of stocks that may be difficult for the average investor to identify. Further, the debate is far from settled. Some researchers reject the January effect altogether.

Until we learn more about the January effect and why it allegedly exists, most investors are probably better off ignoring the January effect when considering investment decisions. When it comes to investing, I recommend analyzing the fundamentals of the company you want to invest in and holding a well-diversified portfolio.

Dr. Scott Jones

Assistant Professor of Finance and Foust Professor of Business