The 2021 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel was awarded jointly to David Card “for his empirical contributions to labour economics,” as well as Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens “for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships”.

The committee honored the three researchers for their work. Collectively, they revolutionized empirical research in economics by providing new approaches to infer causality between variables of interest. Many questions that economists, social scientists, and businesses are trying to answer center around these causal relationships. Does education affect an individual’s future earnings? How do policies such as new immigration or minimum wage laws affect the labor market? Do higher wages increase employee productivity? Or does increased spending on advertising lead to higher sales?

Establishing Causality: Not an Easy Task!

As it turns out, proving that one variable in fact causes changes in another variable is not an easy task. For example, consider a business that wants to know how their spending on advertising affects sales. Let’s take a simple look at the correlation between advertising spending and sales. It is clear that that high advertising spending seems to go hand in hand with high sales. We might then be tempted to conclude that advertising spending is what led to higher sales.

The first problem with this argument is that advertising and sales might be driven by other variables. For example, suppose you sell a product like jewelry, which is a popular gift item for Christmas, Valentine’s Day, or Mother’s Day. While we see increased demand for jewelry around these times of the year, that also appears to be the time when we see increased advertising for these products. Therefore it is difficult to tell whether the increased demand for jewelry during the holiday season. Is it because of the increased marketing efforts or simply because of the seasonal effect?

The second problem is that even after we attempt to control for factors such as seasonality or general economic conditions, we still cannot be sure that higher advertising spending in fact caused the increase in demand. We see that the two variables are moving in the same direction But we don’t know if advertising increases sales, or if higher sales lead to higher advertising budgets.

A Solution to Our Dilemma: Randomized Controlled Trials?

The gold standard for testing the effect of one variable on another is randomized controlled trials (RCT). In a RCT, participants in a study are randomly assigned to a “treatment” or a “control” group. Suppose, for example, you want to test the effectiveness of a new medication. Participants in the treatment group receive the new medication, while participants assigned to the control group receive a placebo. With this research design, we can reduce or even eliminate certain biases that occur if people are allowed to self-select into treatment or control group.

In the social sciences or business, it is often not feasible or ethical to conduct a RCT. For example, our business that wants to know the effect of advertising on sales can’t provide a placebo for advertising spending. Or, consider an economist who wants to study the effect of education on future earnings. They can’t tell parents that their child will only be allowed to attend school through 11th grade instead of finishing high school.

Enter the Nobel Laureates

The three prize winners were honored for pioneering alternatives to RCTs that had the same advantages. As I mentioned above, it is often not feasible or ethical to assign people to treatment and control groups to study the effect of specific policies. Instead, Card, Angrist, and Imbens developed and applied techniques that exploit “natural experiments.” These compare differences between a treatment and control group to make inferences about causal relationships.

One of the first economics studies to pioneer such an approach was a paper by Joshua Angrist and the late Alan Krueger, published in 1991. Angrist and Krueger exploited two features of the US education system to tackle an age-old question: What is the effect of schooling on earnings?

A natural experiment

Angrist and Krueger noticed that prior to the 1990s, students born late in the calendar year were on average younger when they started first grade than children born early in the year. This is because of the cutoff date for starting school being in late December.

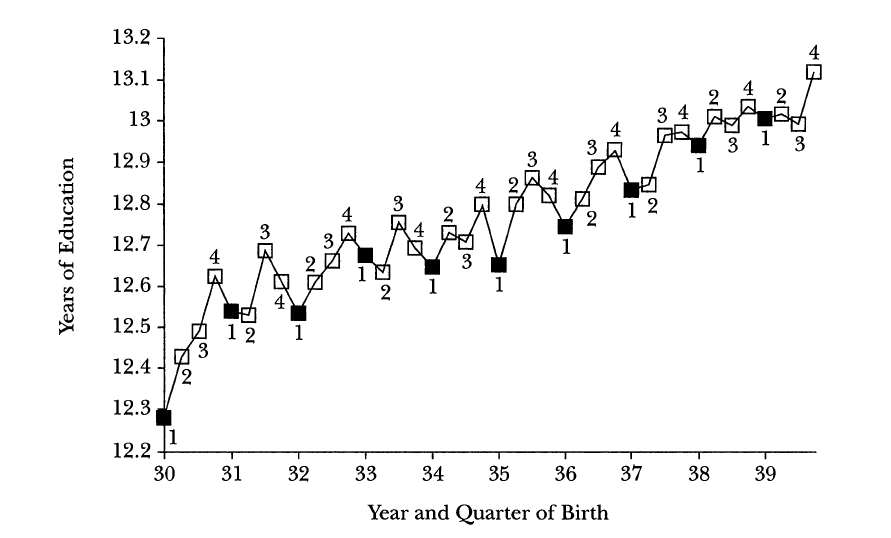

For example, a child born in late December was assigned to first grade, while a child born just a few days later in early January was assigned to kindergarten. Moreover, students could drop out of school once they turned 16. As a result, students who were born late in the year and started school at a slightly younger age, on average stayed in school longer than their classmates who were born early in the year and started school slightly older. The graph below from a review article by Angrist and Krueger (2001) illustrates this.

Source: Angrist and Krueger (2001)

Since when we are born is assigned somewhat randomly, the interaction between the previously discussed school attendance laws essentially randomly assigned students to slightly more or less education. We have a natural experiment!

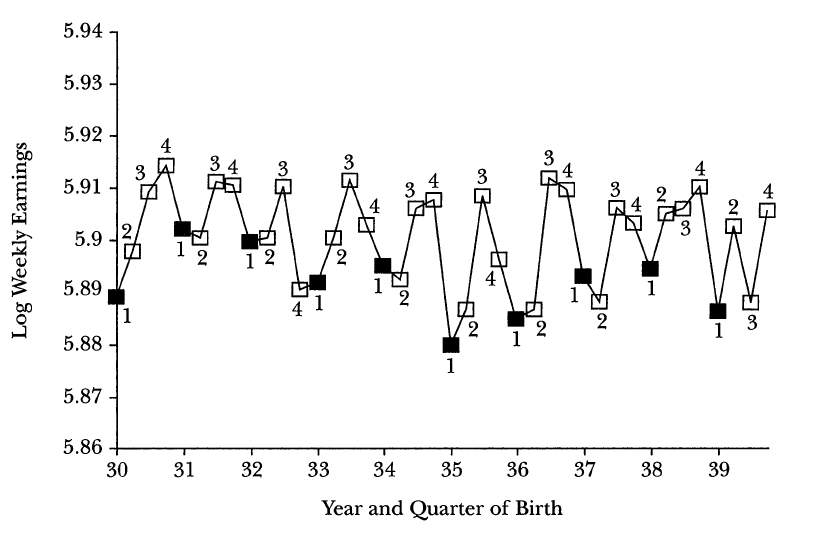

Now, does length of schooling affect earnings? Take a look at the graph below.

Source: Angrist and Krueger (2001)

Just as in the first graph, we see a clear pattern: earnings for students born in the first quarter of the year (who have less schooling on average) are consistently lower than earnings for individuals born in the fourth quarter. For us, the findings are secondary. It’s the method of looking for natural experiments in the world around us to help establish causal relationships that is remarkable!

Finding Differences in Differences

Another interesting natural experiment can be found in the minimum wage study by Card and Krueger (1994). In 1992, New Jersey (NJ) passed a law increasing the minimum wage, while its neighboring state Pennsylvania (PA) did not. Paradoxically, Card and Krueger found that despite the minimum wage increase, employment in fast-food restaurants in NJ did not decrease as expected.

The standard approach to answering questions such as “Did the minimum wage increase affect employment?” was to look at changes in employment before and after the law went into effect. You would then control for other variables that may affect employment.

Card and Krueger, however, chose a different route. The overall economic conditions as well as weather-related effects on fast food demand are expected to be similar in the neighboring states of NJ and PA. What happened in Pennsylvania provides us with a good estimate of what would have happened in New Jersey, had they not increased the minimum wage. In other words, Pennsylvania serves as a natural control group for the treatment group of New Jersey!

Hence, what Card and Krueger did to determine a causal relationship was to look at how employment changed in NJ before and after the minimum wage increase. They compared this difference to how employment changed in PA during the same time frame. The difference between those differences is hence the effect of the minimum wage increase. Pretty clever!

Causality Conclusions

In conclusion, some of the results in these papers have certainly been debated. But they have opened economists’ eyes to natural experiments around them that can be exploited in order to get a step closer to inferring causality. If you are interested in learning more about topics like this, become a Buff and take courses such as Quantitative Analysis or Econometrics!

Dr. Anne-Christine Barthel

Assistant Professor of Economics and Decision Management

For Further Reading on Causality

- Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Does Compulsory School Attendance Affect Schooling and Earnings? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 979–1014. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937954

- Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (2001). Instrumental variables and the search for identification: From supply and demand to natural experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 69-85.

- Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (1994). Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The American Economic Review, 84(4), 772–793. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2118030