The Covid-19 pandemic has reversed much of the progress we have made in addressing the gender gap in occupations since the 1980s. Prior to the pandemic, women were moving up to leadership positions and gaining momentum in participating in the labor force in the U.S. However, the pandemic has hurt women employees the most. The corporations in the U.S. have lost many qualified, working women from all ranks and positions, across sectors. The National Women’s Law Center reported that 5.3 million women have lost their job since the beginning of the pandemic1. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported that unemployment among women quadrupled to 16% in April 2020, and it remained high throughout the year2.

Unemployment and Occupations Held by Women

In particular, the Covid-19 pandemic has negatively impacted occupations with a high prevalence of female workers. A Gallup poll indicated that the following occupations were shattered by the pandemic.

- Health care support

- Personal care and service

- Office and administrative support

- Healthcare practitioner and technical

- Educational instruction and library

- Community and social service

- Food preparation and service

When looking at these specific occupations, women held a larger percentage of these jobs than men did. For example, in health care, 78% of workers were women3. Also, 47% of all job terminations during the pandemic occurred in the areas of leisure, hospitality, education, health services, and retail trade4. These jobs are often referred to as “pink collar” and “service-oriented” occupations4.

Reasons Women Leave the Worforce

In 2020, a Women in the Workplace study by McKinsey and LeanIn.org found several reasons why women are considering taking a lower position or leaving the workforce, including:

- Lack of flexibility. The lack of flexibility at work makes it difficult for women to manage a variety of role responsibilities.

- Being “always on.” This reduces their ability to practice work-life balance and this expectation is unrealistic to fulfill by women who care for children or elderly family members.

- Increased burden. During the pandemic many schools, daycare and after school programs closed and the burden of care-giving for children increased. Also, the cost of childcare became unreasonable with about half of the families reporting spending at least $10,000 a year on childcare5. Mothers also had to provide instruction to their children of age during the pandemic.

- Increased worry. Women worried about being judged negatively due to engaging in care-giving activities.

- Increased discomfort. Women also felt uncomfortable discussing challenging with supervisors and colleagues. For instance, if a supervisor is a male without children, it can make it difficult for them to empathize with women’s child care needs.

- Being blindsided. Supervisors would make blindside decisions at the last minute. Such as being assigned to go to a meeting at a time that was convenient for the company, but not for the employee.

- Partial presence. Women were concerned about not being able to be fully present at work. With so many obligations, women were multitasking, but feeling distracted.

While these reasons are also relevant to fathers, the pandemic hurt women at higher rates, in part, due to gender biases in the workplace. Women in leadership positions can detect subtle microaggressions. For instance, colleagues might see a woman in a leadership position held or fed her baby during a Zoom meeting in a negative light.

Comparing Mothers and Fathers

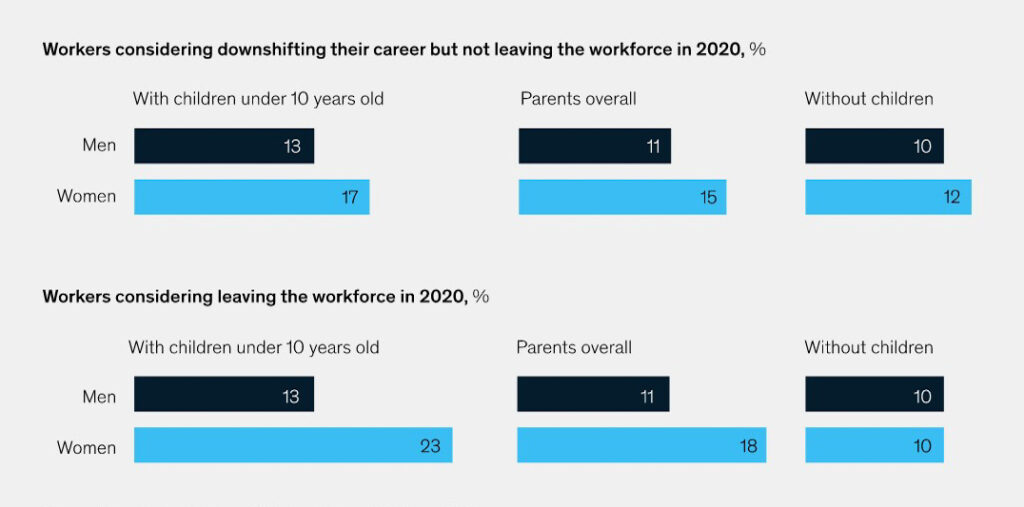

Also, when comparing the rates of men and women, it is clear that women are more likely to consider downshifting or leaving the workforce.

In particular, mothers with children under 10 years old are at risk of leaving the workforce in comparison to fathers. While the pandemic has also affected fathers, the study reports that 25% of women considered downshifting or leaving their careers in comparison to males. The pandemic affected mothers who were also working, women in senior management positions, and Black working women6. The study also reported that mothers with children under 10 in dual-career relationships spent 22 additional hours in household responsibilities such as cleaning, cooking, and doing laundry in comparison to 10 hours spent by fathers7. These growing gender inequities have made it challenging to retain women in the workforce.

Experiences of Working Women During the Pandemic

Subjectively and psychologically speaking, women experienced the pandemic differently from men. In the Women in the Workplace 2020 study, women revealed their personal experiences during the pandemic.

Experience #1

“I don’t talk about my caregiving responsibilities with my boss. Women with children always have some stigma attached to them in the workplace. People might think I don’t work as hard because I have children. I never want that stigma to be attached to me at my work.”

Source: Asian American Woman, Director, Women in the Workplace 2020, McKinsey and Leanin.org, 2020

In this experience, this woman explains her worry that her hard work might not be noted due to her care-giving obligations. The stigma of caregiving can place some women at a disadvantage depending on the culture of the corporate environment. In this quote, the woman also shares that she is uncomfortable sharing her experiences with her boss out of fear of being perceived negatively. This challenge can negatively impact the trust and open communication with her boss.

Experience #2

“We are still expected to meet, if not exceed all of our targets. The Covid-19 pandemic hasn’t affected anything as far as what we’re required to get done. So far, we’ve been able to make our goals, but there is a lot of extra stress. They tell us, ‘You just need to figure it out.’ Delay is not an option.”

Source: Asian American Woman, Director, Women in the Workplace 2020, McKinsey and Leanin.org, 2020

The frustration felt by this woman is evident. The pressure to fulfill workplace expectations at the same level prior to Covid-19 has added stress upon her. She also indicates that there is a lack of flexibility in the deadline. Without flexibility, in completing work tasks, women may feel trapped between a rock and a sword. And, being unhappy with the result.

Experience #3

“This has been the most challenging professional and personal year of my life. I have days where it all feels hopeless. I’ve been thinking about stepping back, which I never did before Covid-19. I’m looking for a role at other companies with a smaller team and shorter hours.”

Source: White Woman, Vice President, Women in the Workplace 2020, McKinsey and Leanin.org, 2020

In this narrative, this woman is sharing her challenges at both the personal and professional level. She is considering leaving her leadership role as Vice President. She indicates being in the job market to look for another job that has reduced work hours so she can better manage her life.

All of these women have similar struggles that have intensified during the pandemic. Challenges may vary across rankings and economic levels. When the pressure becomes too overwhelming, should one become career-oriented or family-oriented? From the data – it looks like many women are choosing their families.

Future Outlook

As we can see, the pandemic has made women reconsider their role in the workforce. We continue to lose many talented and qualified women, especially women of color. Corporations and companies can consider the unique challenges that women might be facing. Leading companies have already taken the initiative to address this issue “head on” by implementing practices and policies that help retain women in the workforce. But, will these efforts retain qualified women throughout the pandemic? Will these unemployed women return to the post-pandemic workforce? Only the future will tell.

References

1 National Women’s Law Center (NWLC). (2021). A year of strength & loss: The pandemic, the economy, & the value of women’s work. Washington, DC.

2 PWC. (2021). Covid-19 is reversing the important gains made over the last decade for women in the workforce – PwC women in work index. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/new-room/press-releases/2021/women-in-work-index-2021.html

3 Rothwell, J., & Saad, L. (2021). How have U.S. working women fared during the pandemic? News Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/330533/working-women-fared-during-pandemic.aspx

4 Smart, T. (2021). In one year, coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc on working women. US News. https://www.usnews.com/news/economy/articles/2021-03-08/in-one-year-coronavirus-pandemic-has-wreaked-havoc-on-working-women

5 Dizik, A. (2021). Women are getting pushed out of the workforce – With few ways to return. Time. https://time.com/nextadvisor/in-the-news/women-in-the-workplace/

6 McKinsey & Company. (2021). Seven charts that show Covid-19’s impact on women’s employment. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/seven-charts-that-show-covid-19s-impact-on-womens-employment

7 McKinsey & Company. (2020). The pandemic’s gender effect. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/five-fifty-the-pandemics-gender-effect