Once Halloween passes, big displays in stores remind us that it is time to start thinking about our Christmas shopping lists. Every year, many of us find ourselves racking our brains over what to get loved-ones, friends, business partners or employees. And maybe you too have found yourself thinking every now and then “Wouldn’t it be easier to just give them the money and let them pick out their own gift?” As an economist, I can tell you that the answer is yes – easier, and actually less wasteful!

When talking to an economist about Christmas, one might expect comments about the positive effect of holiday shopping on the economy overall. Microeconomists however may also point out inefficiencies that can arise from holiday gift-giving.

The Deadweight Loss of Christmas

In 1993, economist Joel Waldfogel published an article titled “The deadweight loss of Christmas”. In this article, Waldfogel illustrates how holiday gift-giving – even though well-intentioned- can lead to economic inefficiencies. Suppose I go to the mall and buy my (imaginary) uncle Joe a $50 tie for Christmas. By making the purchase, it is clear that I think the tie must be worth at least $50. But what if uncle Joe never wears ties? Then this gift is essentially worthless to him and I might as well have burned that $50 bill instead of buying him the tie. This mismatch between how much the gift giver and gift receiver value an item is what Waldfogel refers to as the deadweight loss, a fancy economics term for waste or inefficiency.

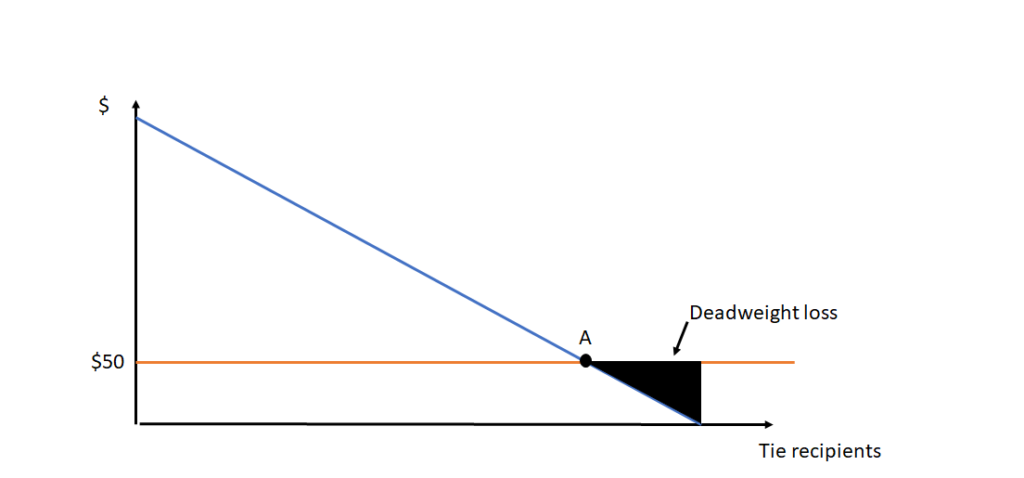

The figure below illustrates this inefficiency. We plot the number of recipients of the tie that I bought my uncle on the horizontal axis and their valuation of said tie on the vertical axis. The result is the blue line, where we sorted them from highest valuation to lowest valuation. The red line shows the cost of the tie, which is $50. Notice that the two lines intersect at point A. All tie recipients to the left of point A actually value the tie at more than $50 – for all of these individuals this was a great gift! But all the tie recipients to the right of point A value it at less than $50, and so for all of these individuals the gift essentially destroys value. If we add all of this lost value up, we get the deadweight loss, illustrated by the black triangle.

How big of a problem is this deadweight loss?

While it is easy to see how gift giving can result in inefficiencies, a natural follow-up question to ask is how big this deadweight loss really is. Are we talking about a significant fraction of the gifts value or just a minor decrease? In his paper, Waldfogel estimates that between a tenth and a third of the value of gifts is destroyed by gift giving. Given that last year’s total holiday gift spending was estimated to top 1 trillion dollars, that’s a significant amount of money if his findings can be generalized to the overall population.

Of course we would also expect the severity of these inefficiencies to be less severe if gift giver and recipient have a close relationship and know each other well. Waldfogel’s findings show that the deadweight loss is relatively small for significant others and parents. Aunts’, uncles’ and grandparents’ gifts however exhibit the highest value lost.

So what do economists give for Christmas?

So, what do economists suggest to solve this dilemma? The answer is to give cold, hard cash. A cash gift is worth the same to the gift giver and gift recipient, and thus no inefficiencies arise. Gift cards are essentially like cash gifts, which makes them another good option if giving cash just doesn’t feel right to you.

In the end, I believe that even most economists don’t take their own advice when it comes to Christmas presents. After all, many of us still enjoy shopping for family and friends and a thoughtfully picked out gift may even be worth more to the recipient than the monetary cost to the gift giver. Just know that if you are struggling to find the right gift for someone and are considering just giving cash or a gift card, you can support your choice with the economic arguments that I have outlined above.

To learn more about how to make decisions like an economist, become a Buff and take economics courses!

Anne Barthel

Assistant Professor of Economics and Decision Management