Pop quiz: Who is the world’s most profitable auto maker? Answer? Toyota. Indeed, again and again, Toyota leads out in net income against other automakers. Moreover, in 2021, the #1 auto maker in the US in terms of sales was not GM, but rather Toyota. It is clear that Toyota leads the way in automobile manufacturing. How is this so? In a word: culture.

Culture is the Key

These numbers signal that there is much we can learn from Toyota. More practically, these numbers also signal that there is much that other auto makers can learn from Toyota. Toyota has maintained this wide gap of success for decades. Yet it is only in recent years that other automakers have admitted that the Toyota Way was superior.

To illustrate, GM and Toyota formed a partnership in the 1980s that allowed GM to directly learn the Toyota Way. They shared a manufacturing facility in the US where Toyota implemented their production system with an open door. This allowed other automakers to observe the whole process, learn firsthand, and replicate the process as they saw fit. Notwithstanding, it took two decades before anybody at GM took Toyota’s principles and values seriously.

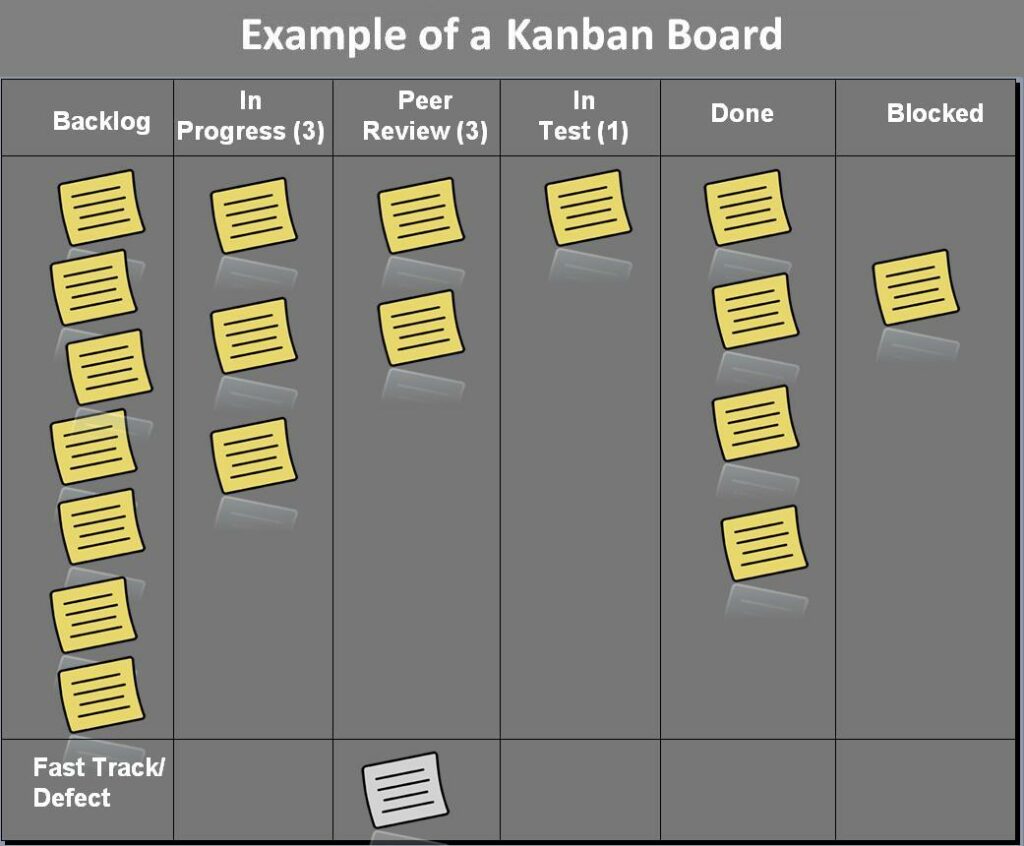

Why? Here is one explanation: When GM tried to implement Toyota’s procedures such as Kanban (i.e., signboard system aimed at achieving just-in-time manufacturing, or JIT), or Heijunka (i.e., evening out the workload across the system), the procedures at first backfired and worsened GM’s financial ratios in the short-to-mid-term. How could one automaker not land the same success as another automaker despite implementing the same procedures? The short answer is because GM did not have a cultural foundation that supported the lean manufacturing processes.

Three Layers of Culture

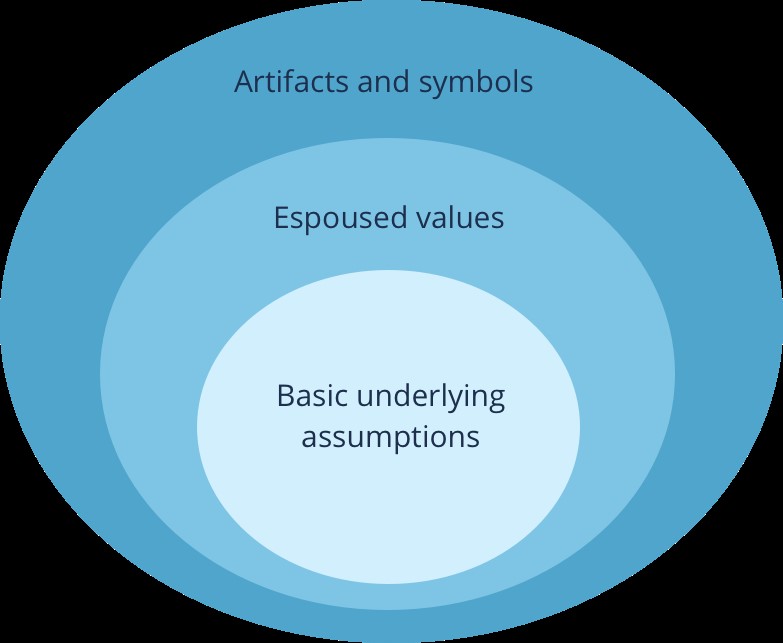

Theory on organizational culture posits that there are three layers of culture, each with their own distinctive definitions and meanings. Starting from the outside and moving inward, we first have the layer of observable artifacts. This layer includes the procedures, behaviors, physical structures, language, etc. that can viewed and somewhat understood if you are an “outsider” such as a customer or competitor.

The middle layer of culture is espoused values. Here we have the values and norms that a company explicitly states, such as those found in a values statement. Finally, the inner layer of culture is basic underlying assumptions. These are shared, taken for granted beliefs that dictate how individuals think and feel about things. The inner layers of culture are difficult to fully understand unless you are an “insider” of the organization.

This framework helps us explain how GM was unable to successfully mimic Toyota’s procedures. Toyota had their procedures—that is, their observable artifacts—supported by aligned layers of espoused values and basic underlying assumptions. In contrast, GM did not.

The Ohno Circle

One famous example of an artifact aligning with Toyota’s culture is the Ohno circle, created by and named after the father of the Toyota Production System, Taiichi Ohno. On one occasion, as recounted in “The Toyota Way,” Ohno was teaching Teruyuki Minoura, the president of Toyota, North America. Ohno instructed Minoura to draw a circle on the production floor and then to “stand in that and watch the process and think for yourself.”

That was it; Ohno didn’t give Minoura any hints about what to watch for. Mr. Ohno left Minoura to his observational duties, and then came back to check on him—eight hours later! Upon Ohno’s return, Ohno asked Minoura what he was seeing, to which Minoura replied, “There were so many problems with the process…” Minoura learned that his time spent in the Ohno circle was well worth it. He discovered handfuls of ways to take their manufacturing to the next level by simply observing the process.

In this example, we can consider the Ohno circle as an observable artifact. We can identify the espoused values as deep observation and deep understanding. Regarding the basic underlying assumptions, we can identify the beliefs that continuous improvement is paramount, and that slow, methodical observation is what leads to success.

The Ohno Circle in America?

The Ohno circle had a hard time catching on at American companies. Can you imagine a president of any American company just standing in a circle and observing for eight hours? What values do we typically espouse in America? Typically, speed and real-time data. What are our typical underlying assumptions? Status and power are paramount; busyness is what leads to success. Backed by strong evidence, I argue that these were the values and beliefs maintained by GM and others at the time, and is the key reason why other automakers were unable to replicate the success despite mimicking Toyota’s process.

The positive side of the story is that US automakers finally came around and took these values and beliefs seriously. Consider Ford Motor Company, who in the early 2000s was rated as the worst in quality, but who in 2010 was rated best in class. During this decade, Ford made its necessary adjustments to its basic underlying assumptions and espoused values, which allowed them to successfully sustain lean manufacturing practices. This was no easy feat, and Ford deserves all the praise it gets for its process improvements. The key for Ford was to align the three layers of organizational culture. Following this alignment, they no longer experienced conflict between its procedures and the deeper layers of culture.

Two Lessons from Toyota

There are two key learning points from the case of Toyota. First, “best practices” don’t always work. Sure, another company may have success with a new technology, production process, or management system. However, this doesn’t mean that your organization will achieve the same success if it acts the same way. Rather than implementing “best practices,“ organizations should instead focus their energy on ensuring that their procedures and behaviors align with their deeper levels of culture.

Second, sustainable culture change requires deep work. Quickly making adjustments to policies or procedures will not have any lasting impact unless beliefs and values also change. This is, of course, easier said than done. However, as I’ve written about before, leveraging environmental forces is crucial for sustainable success, and is thus well worth the effort.

Dr. Trevor Watkins

Assistant Professor of Management & Foust Professor of Business